History

Kamĩrĩĩthũ and Villagization

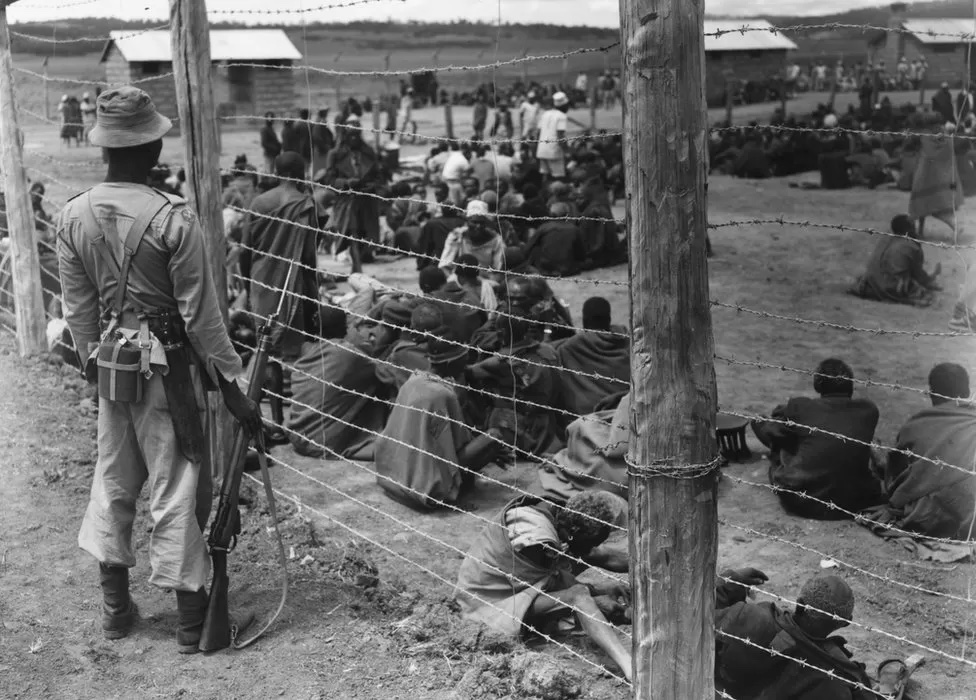

The village of Kamĩrĩĩthũ is located in the semi-rural district of Limuru, in the heart of what was once called the “white highlands.” This part of Kenya is the ancestral homeland of predominantly Kikuyu communities. Many of these communities were dispossessed by the British colonial regime to make space for tea and coffee plantations and lavish plantation homes. Kamĩrĩĩthũ was established by the British colonial regime in response to the anti-colonial uprising led by the Kenya’s Land and Freedom Army during the early 1950s. British armed forces rounded up people and contained them in tightly controlled camps dispersed over the central Kenyan countryside.

Concentration camps built by the British during the anti-colonial war in the 1950s (Source: BBC)

But the area around Kamĩrĩĩthũ was marred by colonialism long before. The nearby railway station of Limuru became an important node of the plantation economy that developed in the first half of the 20th century. Much of the world-famous tea and coffee of the region was shipped through Limuru station. The station also became an ideal location for the establishment of one of the first Kenyan factories, the Bata Shoe Company, in 1938.

Limuru tea plantations (Photo: Kitata, 2022)

Photo of Limuru station (Photo: Cupers, 2022)

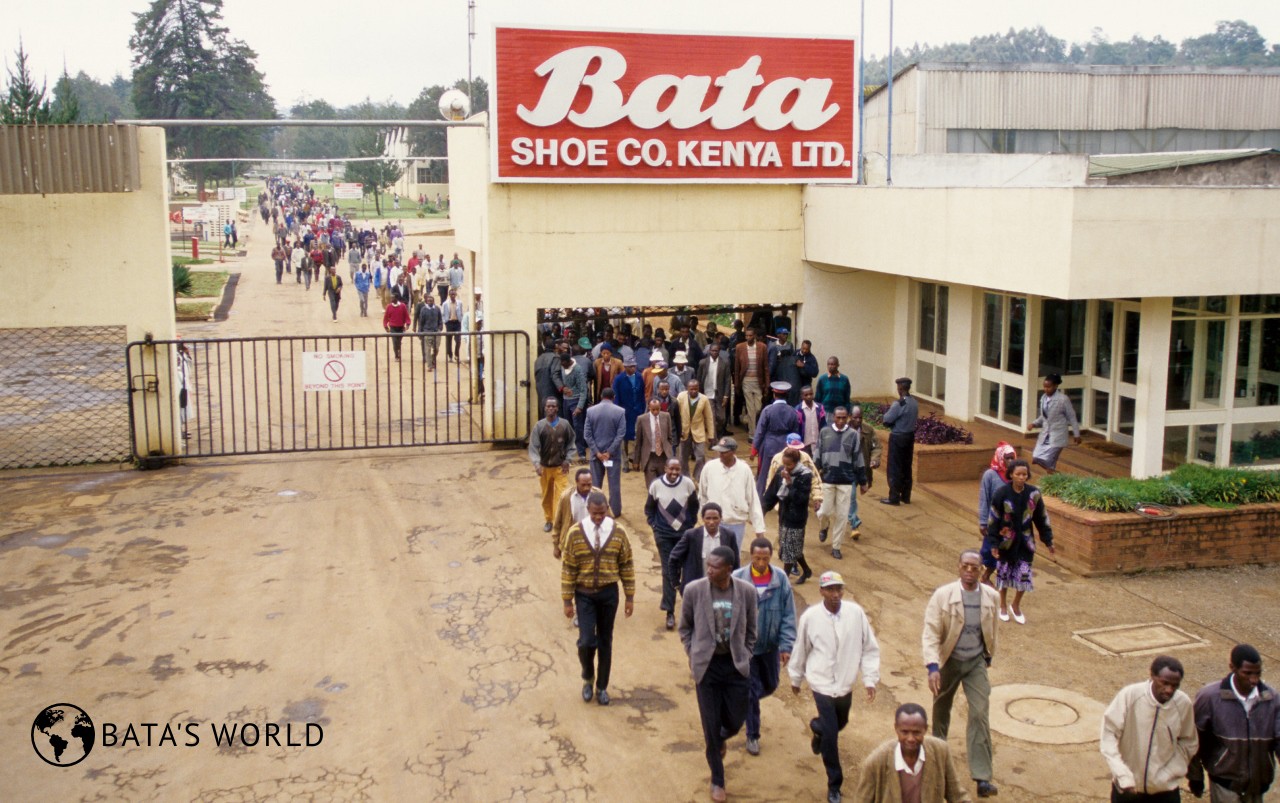

Photo of Limuru station (Photo: Cupers, 2022)Historians have celebrated this multinational company’s progressive approach to factory labor. And it is true that Bata company towns built in the Czech Republic, Canada and elsewhere are marvels of modernist urbanism. The Bata facilities in Limuru, Kenya, were also equipped with housing for some employees as well as some amenities such as sports grounds and a social club. Yet these were not available to the many casual workers, who constituted a significant portion of the labor force. Many came from forced resettlement villages such as Kamĩrĩĩthũ.

Bata shoe factory in Limuru (Source: Bata’s World)

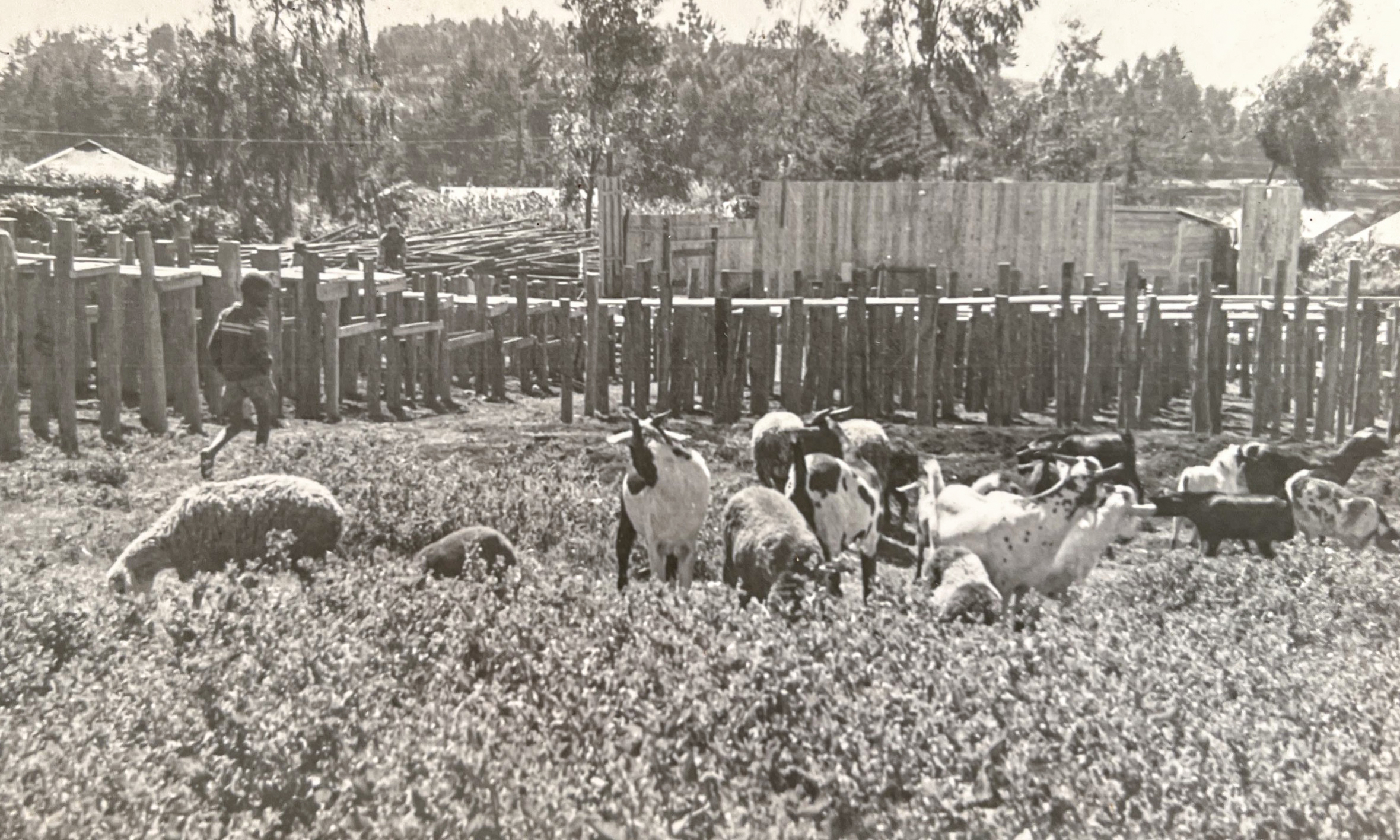

The site of Kamĩrĩĩthũ was originally inhabited and cultivated by Kikuyu families, and Clement Warorua Kimani explained to us that Kamĩrĩĩthũ owes its name to this nearby swamp. In the course of the British colonial war, these families were dispossessed to make space for one of the many forced resettlement and detention camps that dot the region.

The site of Kamĩrĩĩthũ was originally inhabited and cultivated by Kikuyu families and owes its name to this nearby swamp, as Clement Warorua Kimani explains (Photo: Cupers & Kitata, 2022)

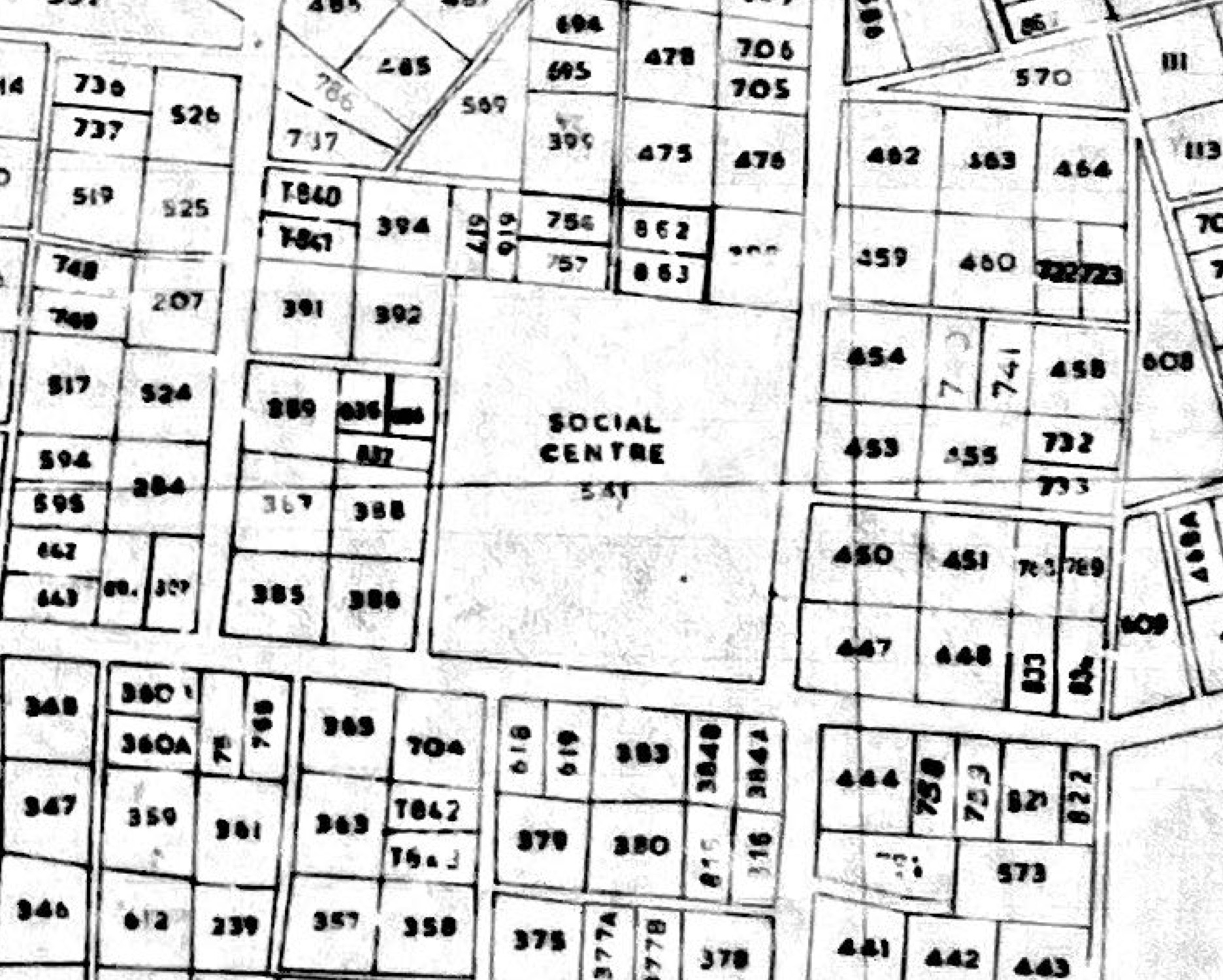

Kamĩrĩĩthũ land ownership map, showing a grid of small plots with an open space at the center (Source: Kiambu archive)

Kamĩrĩĩthũ land ownership map, showing a grid of small plots with an open space at the center (Source: Kiambu archive)Kamĩrĩĩthũ was one of these forced resettlement camps. Its land ownership map, from the Kiambu district archives, shows that each plot is a roughly standard size, with an open space at the center. The British had left this space as a community area to provide otherwise bare camps with minimal amenities. People in Kamĩrĩĩthũ refer to it as the “social hall,” and they used it for community gatherings in the years after Kenya’s independence. On one end of this open space was a hut, likely built by the British.

Adult literacy classes (Photo by Sultan Somjee, courtesy of George Kabonyi)

In 1976, a Community Educational and Cultural Centre was established here to offer literacy classes primarily to local women. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o himself reported, it was a local government official, Ms. Amoni, who informed Ngugi in 1976 that this piece of community land could be grabbed at any time, and should be claimed permanently for community use. Together with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii they conceived the establishment of the theatre on the site as a collaborative process of construction that would involve the villagers.

The Open-Air Theatre and the Play

Kamĩrĩĩthũ theatre (Photo by Sultan Somjee, courtesy of George Kabonyi)

Kamĩrĩĩthũ theatre (Photo by Sultan Somjee, courtesy of George Kabonyi)The villagers built the open-air theatre themselves, reflecting a shared sense of ownership and purpose of the project, and the close relationship of the play with the social environment through which the performance space emerged.

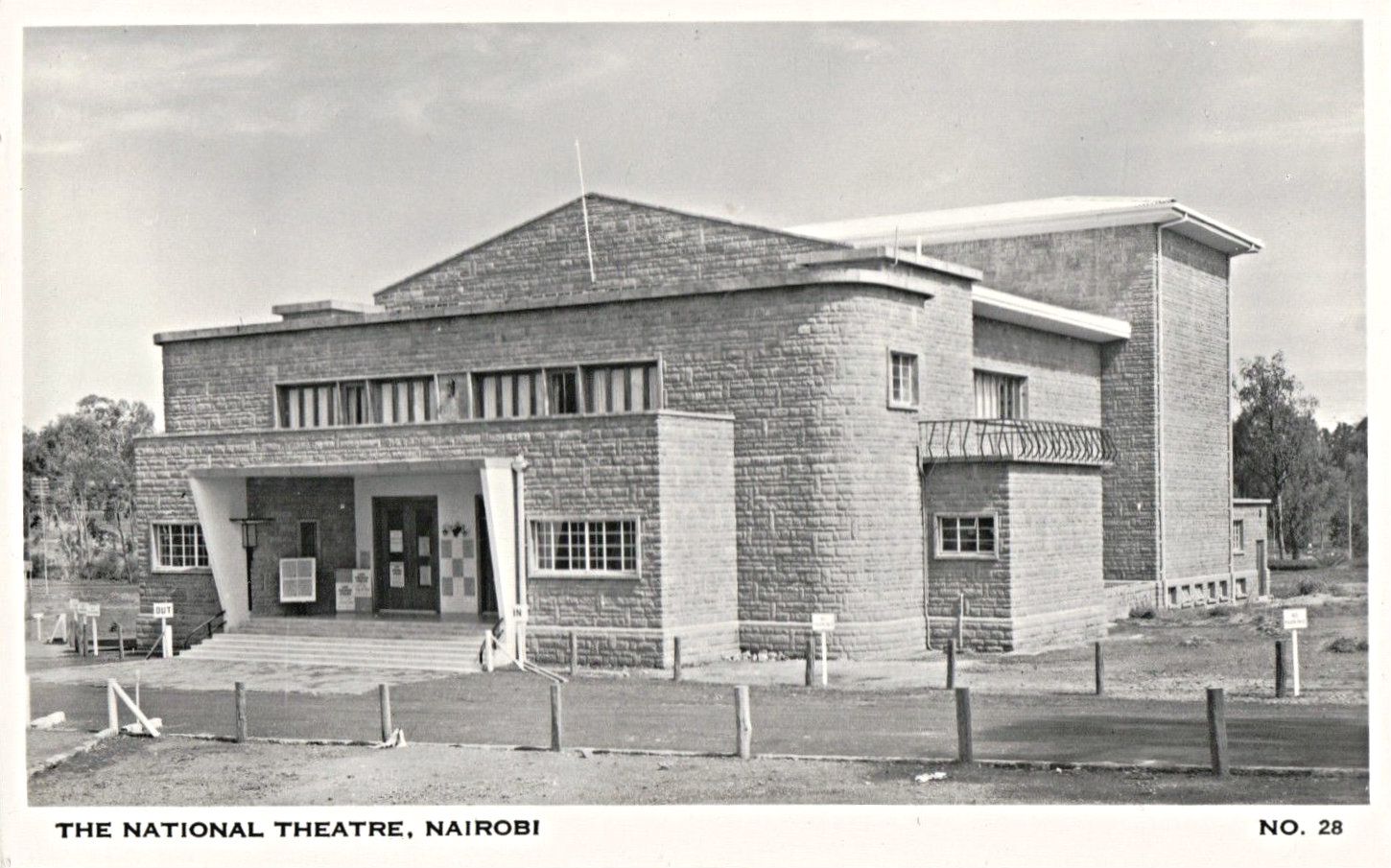

Kenya National Theatre in Nairobi, ca. 1952 (Photo courtesy of Mary Evans/Pharcide)

In contrast with the bourgeois theatre performances in Kenya’s National Theatre, Kamĩrĩĩthũ’s open-air theatre design imbued a sense of openness and freedom, and the proximity of the players to their audience and to the surrounding environment contrasted with the prison-like working conditions in the factory. In this context, the actors themselves acted out their own local conditions of exploitation.

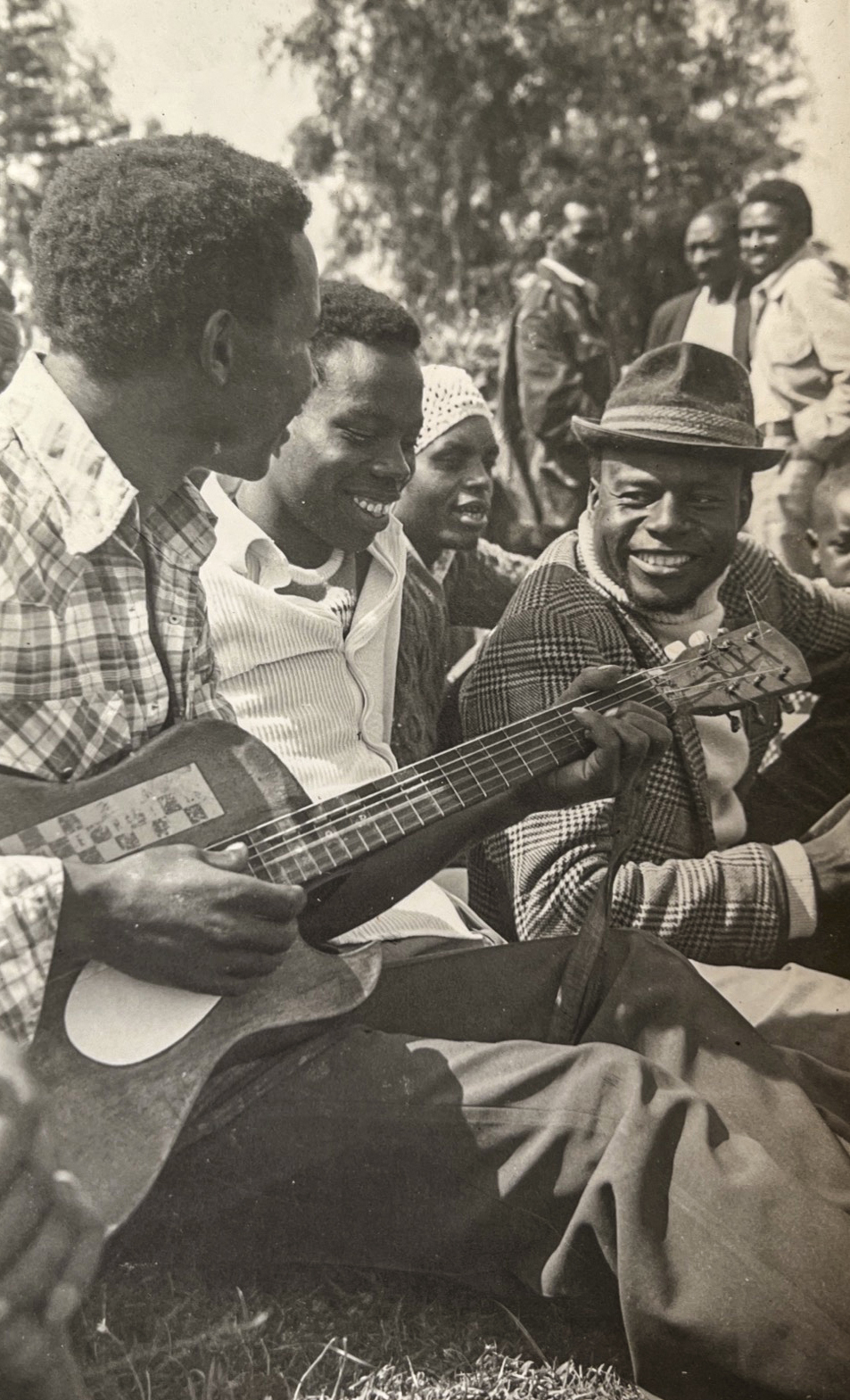

Music rehearsal at Kamĩrĩĩthũ (Photo by Sultan Somjee, courtesy of George Kabonyi)

Music rehearsal at Kamĩrĩĩthũ (Photo by Sultan Somjee, courtesy of George Kabonyi)The play directly addressed the exploitative conditions of the local agricultural and manufacturing industry, epitomized by the Bata Shoe Company and the nearby tea plantations. It effectively showed ordinary Kenyans not only the conditions of their exploitation, but also gave them role models for defiance and revolutionary action against what they experienced as an oppressive system not much different from British colonial rule.

To regain their humanity, the villagers needed to stand up and boycott wage labor, so the play suggested. That is in fact exactly as they did: factory workers in the Limuru district had organized multiple labor strikes during the 1960s and 1970s. The play conveyed existing experiences of injustice and served as a public indictment of those looting the wealth of the nation, left by the British colonialists in the hands of an irresponsible elite who sought to continue exercising their economic interests through local proxies.

The contemporary built environment of Limuru district continues to reflect economic disparities. Adjacent to the Kamĩrĩĩthũ settlement, one can still find the same tea plantations. The larger district of Limuru is divided into two opposite realms separated by the colonial railway. On the one hand, a sector in which those dispossessed of their land are “piled up on top of each other” (as Fanon described the spatial order of colonialism in The Wretched of the Earth) on the other hand, a sector of tarmacked roads, well-watered crops, and lavish plantation homes.

Running along the now-defunct railway, which delivered tea and Bata shoes to Nairobi and beyond, is the Nairobi-Nakuru road—part of the Trans-African Highway which Kenyatta’s regime presented as an instrument of Pan African integration. Despite its dreams of African development and mobility, as Kenny Cupers and Prita Meier have shown, the highway entrenches the segregated structure of Limuru, revealing the endurance and renewal of colonial relations of power. Every day, workers cross this spatial divide on their way to work and back.

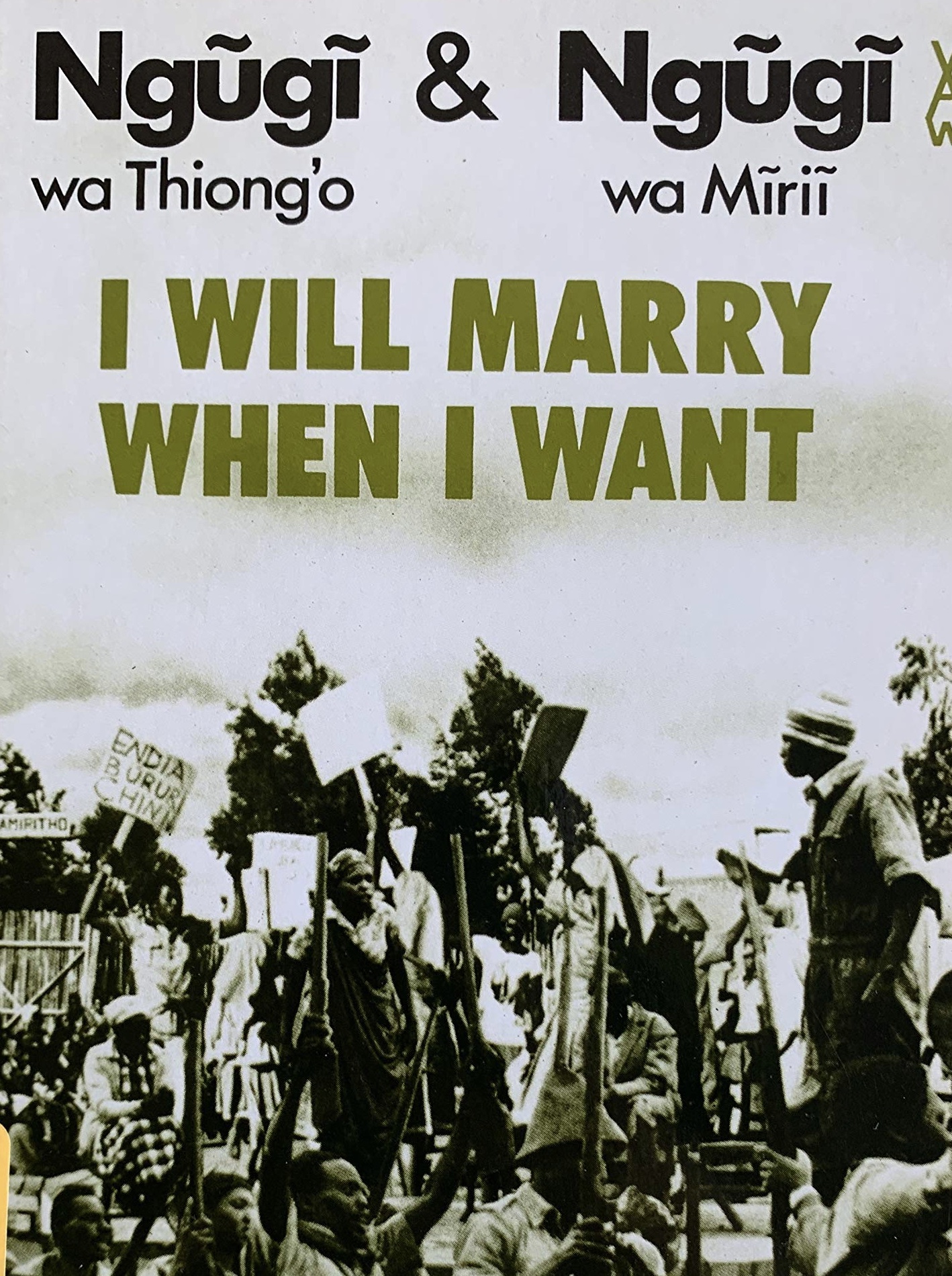

Cover of the book I will marry when I want (Ngaahika Ndeenda), by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii

Cover of the book I will marry when I want (Ngaahika Ndeenda), by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Ngũgĩ wa MiriiThis postcolonial spatial condition is also expressed in the play: Wangeci, the wife of Kiguunda, remarks that the son of the rich Kioi, John Muhuuni, comes to pick up Gathoni, Kiguunda’s daughter, but never enters the house. This conveys players’ awareness of how infrastructure structures their relation to power.

The intimate relationship between the built environment of Limuru district and the performance space of Ngaahika Ndeenda shows the forces that define the lives of Kamĩrĩĩthũ. It gives a sense of the social and environmental injustices which the community theatre sought to contest.

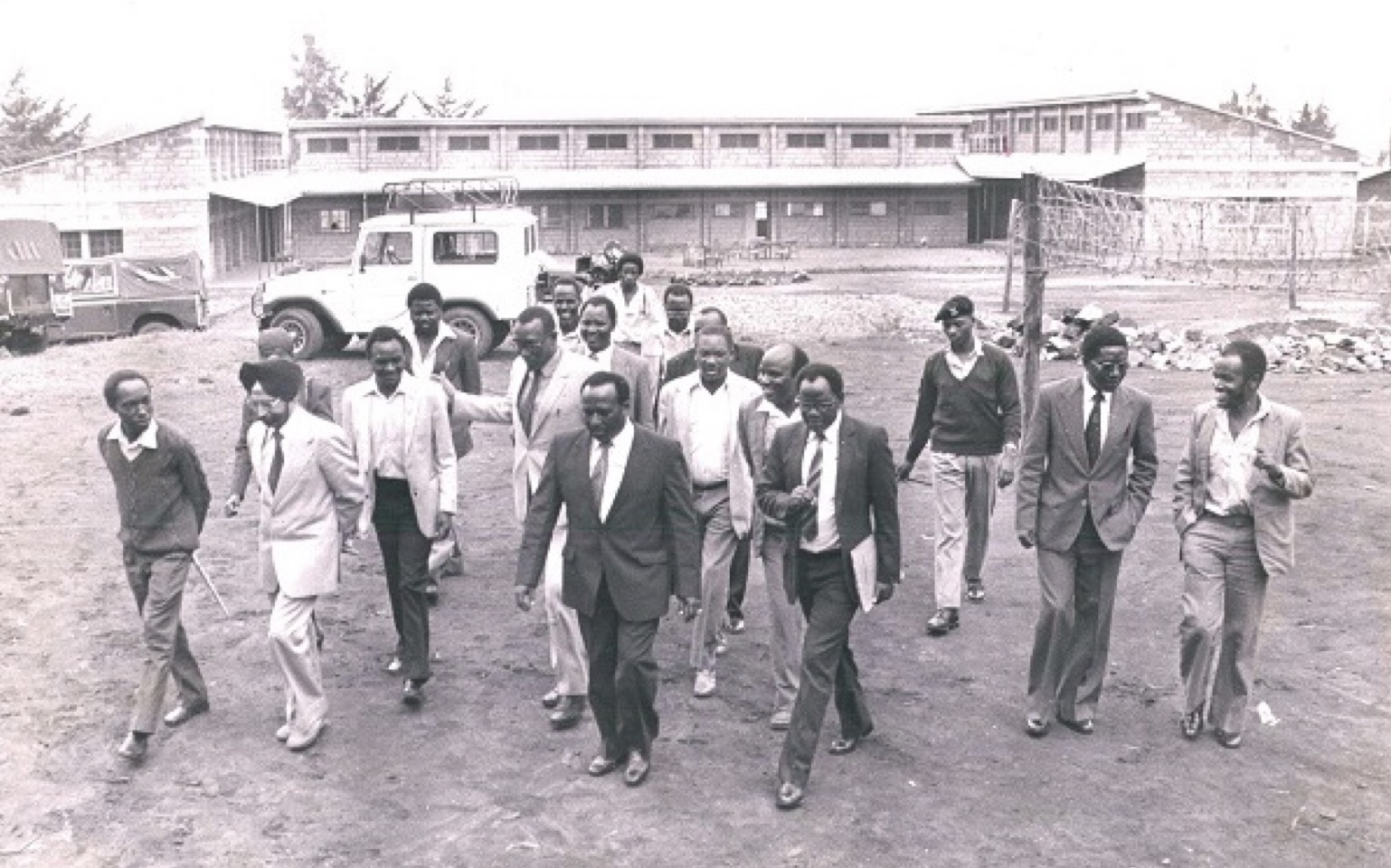

Inauguration of the Kamĩrĩĩthũ polytechnic, ca. 1985 (Source: Nation Media)

What follows is well known. After the government prohibited the performance of Ngaahika Ndeenda, and imprisoned Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o without trial in 1977, the Kamĩrĩĩthũ theatre stood empty for several years. Yet by 1982, the performers had regrouped and rehearsed for a new play by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Maitu Njugira (Mother Sing for Me), this time at the National Theatre in Nairobi. Shortly before the performances were to take place, however, the government withdrew the performance license, and soon after, ordered the demolition of the open-air theatre at Kamĩrĩĩthũ village. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii went into exile. On the site of the demolished open-air theatre, the government erected a polytechnic. While this provided educational opportunities, it also silenced the community and erased the Kamĩrĩĩthũ theatre experience.

Afterlives

Since the 1970s, Kamĩrĩĩthũ village has become increasingly densely occupied, and the informally built structures around the polytechnic speak of the enduring legacies of injustice. The scarcity of land in the village is an enduring consequence of colonial and postcolonial dispossession. The site of the former theatre also housed some squatter homes. After the demolition of the theatre, the government moved some of these squatters, while others moved to nearby spaces reserved for roads and were joined by other migrants. The contemporary village is strewn with semi-permanent iron sheet structures, on road reserves and otherwise unclaimed land. These structures form a large part of Kamĩrĩĩthũ housing environment which residents refer to as shauri yako, Kiswahili for “it is up to you.”

“Shauri yako” settlement in Kamĩrĩĩthũ (Photo: Cupers, 2022)

Kamĩrĩĩthũ has witnessed the emergence of new economic activities and forms of sociability. Much of this is due to the Trans-African highway, which does not only play a segregative role, but also an economically generative one. Kamĩrĩĩthũ is now known as far as Uganda, as a center for truck repair, and the local association of small businesses has been a fast-growing engine of employment for the surrounding area. As such, the highway has turned Kamĩrĩĩthũ into a cosmopolitan yet still semi-rural node, and its inhabitants now hail from across the country and from as far as Burundi, Uganda and the DRC.

Kamĩrĩĩthũ association of small businesses (Photo: Kitata, 2022)

An Alternative Architecture for Decolonization

The history of Kamĩrĩĩthũ shows not only how villagers responded to forced resettlement and colonial violence. It also shows how they worked against enduring legacies of injustice and how they imagined and built another future. To understand the role of the built environment in African decolonization, researchers have tended to focus on monumental and state-led building projects, ironically mostly designed by European and other international architects. This scholarship tends to foreground an architectural modernism infused with colonial and developmental logics, which demonstrates the contradictions of the African independence era. African struggles for decolonization, however, were hardly confined to state-led processes of nation-building shaped by global Cold War politics. The Kamĩrĩĩthũ open-air theatre offers a case for exploring the alternative architectural practices at the heart of this struggle.

By analyzing the Kamĩrĩĩthũ theatre not only as a cultural or political event but also as a specific architectural intervention within a complex historical environment, our research contributes to scholarly efforts to develop more African-centered understandings of the continent’s architectural history, one that looks beyond the colonial and developmentalist world of professional architecture (and its racial renderings of African vernaculars) in order to foreground the agency, experience and meaning-making practices of non-elites. We do so by exploring collaborative processes of architectural and spatial production. As open-air theatre aimed to foster political consciousness amongst its players and audience, we foreground the role which the built and natural environment played in this pedagogical process.

Architectural scholarship on decolonization continues to be limited by inherited modes of academic research and publication. Grounded in collaborative work and community engagement, this project aims to expand the epistemological basis of architectural history, so that an alternative architecture for decolonization can become visible.

Written by Kenny Cupers and Makau Kitata, March 2023

An extended version of this account is forthcoming:

Makau Kitata and Kenny Cupers, “Situating Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Theatre and its Afterlives” in:

The Routledge Handbook of Architecture, Urban Space and Politics, Vol II: Ecology, Social Participation & Marginalities,

edited by Nikolina Bobic and Farzaneh Haghighi.

︎

Selected

Bibliography

Björkman, Ingrid. Mother, Sing for Me: People’s theatre in Kenya. London: Zed Books, 1989.

Brathwaite, Kamau. “Limuru and Kinta Kunte.” In Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong'o: Texts and Contexts, edited by Charles Cantalupo (Africa World Press, 1995)

Court, David. “Dilemmas of Development: The Village Polytechnic Movement as a Shadow System of Education in Kenya” Comparative Education Review 17, no. 3 (Oct. 1973): 331- 349.

Crinson, Mark. “’Compartmentalized World:’ Race, Architecture, and Colonial Crisis in Kenya and London.” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020

Cupers, Kenny, and Prita Meier, “Infrastructure between Statehood and Selfhood: The Trans-Africa Highway” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 79, no.1 (2020): 61-81;

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Gikandi, Simon. “Performance and Power: The Plays.” In Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000)

Kariuki, Josiah Mwangi, ‘Mau Mau’ Detainee: The account by a Kenya African of his experiences in detention camps, 1953–1960 (Nairobi, Oxford University Press, 1975)

Kidd, Ross. “Popular Theatre and Popular Struggle in Kenya: The Story of Kamiriithu” Race and Class 24, 3 (1983): 287-304.

Klingan, Katrin, and Kerstin Gust, eds., A Utopia of Modernity: Zlín — Revisiting Bata’s Functional City (Berlin: Jovis, 2009)

Lovesey, Oliver. “Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Postnation: The Cultural Geographies of Colonial, Neocolonial, and Postnational Space.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 48, no. 1 (2002): 139-168

Maina wa Kinyatti, Mwakenya: The Unfinished Revolution (Mau Mau Research Centre. Nairobi, 2014)

Muhia, Mugo. "Choru Wa Mũirũrĩ: Reflections on the Kamĩrĩĩthũ Experience." In African Theatre 13: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Wole Soyinka, edited by Banham Martin, Osofisan Femi, and Njogu Kimani (Boydell & Brewer, 2014): 37-41.

Muriithi, Kiboi, Peter Ndoria, War in the Forest (Nairobi, East African Publishing House, Uniafri, 1971).

Mwendwa, Suki Kaloo Kathuka. “A Design Approach to Facilitating The Village Polytechnic in Kenya” (Master Thesis, Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University, 1985).

Ndĩgĩrĩgĩ, Gĩchingiri. “Kenyan Theatre after Kamĩrĩĩthũ.” TDR (1988-) 43, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 72–93.

Ndĩgĩrĩgĩ, Gĩchingiri. “Kamĩrĩĩthũ in Retrospect.” In African Theatre 13: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Wole Soyinka, edited by Banham Martin, Osofisan Femi, and Njogu Kimani (Boydell & Brewer, 2014): 53-59.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. Epistemic Freedom and Decolonization in Africa (Routledge: London, 2018)

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii. I Will Marry When I Want (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational Books (1980)

Ngũgĩ wa Thiongo. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (London: James Currey / Nairobi: Heinemann, 1986)

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The Making of a Rebel: A Source Book in Kenyan Literature and Resistance (London: Hans Zell, 1990)

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, “Enactments of Power: The Politics of Performance Space” TDR 41, 3 (1997): 11-30.

Ginger Nolan, “Quasi-Urban Citizenship: The Global Village as ‘Nomos of the Modern’,” The Journal of Architecture 23, no.3 (2018): 448–470.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, 1972): 326

Ukaegbu, Victor. “Re-Contextualising Space Use in Indigenous African Communal Performance” in: Kene Igweonu and Osita Okagbue, eds. Performative Inter-Actions in African Theatre 3: Making Space, Rethinking Drama and Theatre in Africa (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2013): 29-50

Wanjala, Ed. “The Village Polytechnic Movement in Kenya” Prospect: UNESCO Quarterly Review of Education V, 3 (1975): 414-417